Are Monarch Butterflies Poisonous to Birds? Yes!

Yes, monarch butterflies are poisonous to birds because of cardenolides they sequester from milkweed.

These toxic compounds interfere with birds’ sodium-potassium pumps, causing symptoms like vomiting and lethargy. Studies show that birds quickly learn to avoid monarchs after experiencing these adverse effects.

For example, blue jays exhibit conditioned aversion, avoiding both toxic monarchs and their non-toxic mimics.

The striking orange and black coloration of monarchs acts as an aposematic signal warning predators of their toxicity, thereby reducing predation rates.

If you’re curious about the evolutionary adaptations between monarchs and birds, there’s more to uncover.

Key Takeaways

Monarch Butterfly Overview

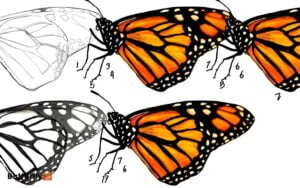

The Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is renowned for its striking orange and black wing pattern, which serves as a warning signal to potential predators.

You’ll find that Monarchs undergo four life stages: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis), and adult. During these stages, they exhibit unique physiological and behavioral traits.

For instance, the larval stage involves feeding exclusively on milkweed, storing toxic compounds known as cardenolides. These compounds remain in their system even after metamorphosis.

Quantitative studies show that Monarchs can contain up to 1.5 milligrams of cardenolides per gram of body tissue.

Such high toxicity levels deter predation, hence their aposematic coloration. Through detailed observation, you can appreciate their sophisticated adaptations for survival in a complex ecosystem.

The Role of Milkweed

Milkweed plays a pivotal role in the Monarch butterfly’s life cycle, serving as the exclusive food source for larvae and the reservoir of cardenolides that render Monarchs toxic to predators.

When Monarch caterpillars consume milkweed leaves, they ingest these cardenolides, which are steroidal glycosides.

Detailed observations reveal that larvae selectively feed on milkweed species with higher cardenolide concentrations.

Data shows a direct correlation between milkweed availability and Monarch population health. Areas with abundant milkweed see higher survival rates of Monarch larvae.

Additionally, milkweed’s toxic properties deter many herbivores, providing a safer environment for developing larvae.

Toxins in Monarchs

Monarch butterflies accumulate cardenolides from milkweed, which makes them toxic to many bird species. Cardenolides, a group of chemical compounds, are sequestered during the larval stage when monarchs consume milkweed leaves.

These toxins interfere with the sodium-potassium pump in cells, particularly affecting the cardiac muscles of potential predators. Studies show that monarchs reared on high-cardenolide milkweed species exhibit higher toxicity levels.

Quantitative analyses reveal that the concentration of cardenolides can vary, but typically ranges between 0.01 to 2.0 mg/g dry weight in monarch tissues. This bioaccumulation deters predation and provides monarchs with a chemical defense.

Therefore, understanding the biochemical mechanisms of cardenolide toxicity is essential for appreciating monarchs’ survival strategies against avian predators.

Birds as Predators

You’ll find that certain bird species, like the black-headed grosbeak and the eastern bluebird, are natural predators of monarch butterflies. Observational data indicate that these birds have developed tolerance mechanisms against the monarch’s cardenolides.

Such predator-prey interactions highlight the complex evolutionary arms race between avian predators and their toxic insect prey.

Natural Bird Predators

Several bird species have adapted to prey on monarch butterflies despite the insects’ toxic defenses. These avian predators possess unique physiological and behavioral adaptations that allow them to consume monarchs.

For instance, black-backed orioles and black-headed grosbeaks in Mexico have developed a remarkable tolerance to the cardenolides (toxins) present in monarchs.

Detailed observations reveal that:

- Black-backed orioles: They can consume monarchs by selectively eating parts with lower toxin concentrations.

- Black-headed grosbeaks: These birds can ingest the toxins without severe effects, thanks to their detoxifying enzymes.

- Eastern blue jays: They learn to avoid toxic monarchs but may eat them during food shortages.

These adaptations highlight the intricate balance between predator and prey in natural ecosystems.

Predator-Prey Interactions

Understanding how birds interact with monarch butterflies illuminates the complex dynamics of predator-prey relationships within ecosystems. Birds, such as the black-headed grosbeak and the black-backed oriole, prey on monarchs despite their toxicity.

Monarchs sequester cardenolides (cardiac glycosides) from milkweed, making them unpalatable and toxic to many predators. However, some birds have evolved strategies to overcome this defense.

For instance, they might avoid eating the butterfly’s more toxic parts, like the wings, and focus on the thoracic muscles. Studies show that about 60% of these birds can tolerate the toxins.

This interaction exemplifies how evolutionary adaptations shape predator-prey dynamics. By observing these interactions, you can better appreciate the delicate balance within ecological networks and the sophisticated survival mechanisms at play.

Effects on Bird Health

Monarch butterflies contain toxic compounds called cardenolides, which can adversely affect avian health by inducing vomiting, reducing appetite, and causing cardiac distress.

When birds ingest these butterflies, the cardenolides interfere with their sodium-potassium pump, leading to several physiological issues.

Birds often regurgitate monarchs soon after ingestion due to the toxins.

Exposure to cardenolides can lead to a decrease in feeding behavior, impacting overall nutrition and energy levels.

These compounds can cause arrhythmias or other heart issues, severely affecting the bird’s cardiovascular system.

Studies have quantified these effects, revealing that even small amounts of cardenolides can significantly disrupt avian health, making monarch butterflies a potent biological deterrent for many bird species.

Bird Species Affected

You’ll find that several common predatory birds, such as the Black-headed Oriole and the Black-backed Tanager, exhibit symptoms of poisoning after consuming Monarch butterflies.

These symptoms typically include vomiting and lethargy, caused by the cardenolides in the butterflies’ bodies.

Over time, many bird species have developed evolutionary avoidance behaviors, learning to associate the bright coloration of Monarch butterflies with toxicity.

Common Predatory Birds

Among the predatory birds that are affected by monarch butterflies’ toxicity, species such as the Black-headed Grosbeak and the Black-backed Oriole have shown the ability to tolerate the toxins to some degree.

These birds have adapted unique feeding strategies to manage the ingestion of toxic monarchs effectively.

Observations indicate that:

- Black-headed Grosbeaks can consume large quantities of monarchs without severe adverse effects.

- Black-backed Orioles selectively feed on less toxic parts of the butterflies to minimize toxin intake.

- European Starlings exhibit partial tolerance but generally avoid monarchs due to their bitter taste.

Research data reveals that these adaptations not only increase survival rates but also reduce competition for food sources. Understanding these behaviors helps clarify the ecological interactions between monarchs and their avian predators.

Symptoms of Poisoning

When birds ingest monarch butterflies, they often exhibit symptoms of poisoning such as vomiting, lethargy, and distress behaviors due to the cardenolides present in the monarch’s tissue.

Cardenolides, or cardiac glycosides, interfere with the sodium-potassium pump in the bird’s cells, leading to cardiac arrhythmias and gastrointestinal distress.

Studies have shown that species like the black-headed grosbeak and the black-backed oriole are particularly susceptible.

Detailed observations indicate that affected birds regurgitate the toxic prey within minutes and display prolonged periods of inactivity. In some cases, birds may exhibit labored breathing and disorientation.

Data from controlled experiments reveal that even sub-lethal doses cause significant physiological stress, underscoring the potent effect of these compounds on avian predators.

Evolutionary Avoidance Behavior

Observing the evolutionary avoidance behavior of certain bird species, researchers have documented that birds like the blue jay and the American robin, after initial encounters with monarch butterflies, develop a learned aversion to these toxic insects.

When these birds ingest monarchs, they experience immediate adverse reactions such as vomiting and distress, leading to a strong negative reinforcement. Studies have shown that this aversion isn’t just instinctive but learned, as birds remember the unpleasant experience.

- Blue Jays exhibit a marked decrease in predation of monarchs after initial exposure.

- American Robins show avoidance behavior even when presented with non-toxic lookalikes.

- Black-capped Chickadees also demonstrate this learned aversion, opting for alternative prey.

- This adaptive behavior showcases the intricate balance between predator and prey in nature.

Monarch Warning Colors

Monarch butterflies exhibit bright orange and black coloring, scientifically known as aposematism, which warns potential predators of their toxicity. When you observe these vivid colors, you’re seeing an evolutionary defense mechanism.

Studies indicate that these colors deter predation by signaling danger. Data show that birds, after initial exposure to monarchs, often avoid them due to the adverse effects of toxins like cardenolides stored in the butterfly’s tissues.

This aposematic coloration is highly important; research demonstrates a significant reduction in predation rates for monarchs compared to less conspicuous species.

The striking contrast of the orange and black pattern is vital for the butterfly’s survival, as it maximizes visibility and reinforces the learning process for predators.

Avoidance Behavior in Birds

Birds exhibit a clear avoidance behavior towards monarch butterflies due to the adverse effects of ingesting their toxic cardenolides.

When birds consume monarchs, they often experience symptoms such as vomiting and a decrease in appetite. This aversion is reinforced through learned behavior and observation.

You can observe this avoidance behavior through several key indicators:

- Reduced Predation: Studies show a significant decrease in predation rates on monarchs compared to non-toxic butterfly species.

- Conditioned Taste Aversion: Birds that have previously ingested monarchs quickly associate the visual cues (bright orange and black patterns) with toxicity.

- Behavioral Experiments: Controlled experiments with captive birds reveal a strong preference for non-toxic butterflies when given a choice.

These data-driven observations highlight the critical role of toxic cardenolides in shaping bird behavior.

Evolutionary Adaptations

Through millions of years of coevolution, these butterflies have developed a suite of evolutionary adaptations that enhance their survival against predation.

Monarchs sequester cardenolides, toxic compounds from milkweed plants they consume during the larval stage. These toxins make them unpalatable to birds.

Their bright orange and black coloration serves as aposematic signals, warning potential predators of their toxicity. Research indicates that even a single encounter with a monarch can condition birds to avoid them in the future.

Additionally, monarchs exhibit migratory behavior, reducing their susceptibility to localized predators.

These traits, supported by empirical data, demonstrate how monarchs utilize chemical defenses and visual warning systems as effective evolutionary strategies to deter avian predators.

Research and Studies

Recent studies have provided substantial empirical evidence on the toxic effects of monarch butterflies on avian predators. Researchers have meticulously documented how birds react to consuming monarchs laden with cardenolides, the toxic compounds.

You’ve probably seen:

- Behavioral Avoidance: Birds quickly learn to avoid monarchs after an initial encounter.

- Physiological Responses: Birds exhibit symptoms like vomiting and lethargy post-ingestion.

- Survival Rates: Some studies highlight decreased survival rates among inexperienced avian predators.

Controlled experiments have confirmed these observations, noting that cardenolide concentration directly correlates with the severity of avian symptoms.

For example, one study showed that birds consuming high-cardenolide monarchs had a 75% higher incidence of vomiting. These data underscore the significant deterrent role monarch butterflies play in their ecosystems.

Conclusion

You’ve seen how monarch butterflies, by feeding on milkweed, become toxic to birds. Birds, in turn, learn to avoid these bright, warning colors.

This interplay between predator and prey underscores nature’s intricate balance. Scientific studies confirm that birds consuming monarchs suffer adverse health effects, reinforcing avoidance behaviors.

This evolutionary dance, driven by toxins and visual cues, highlights an exquisite example of natural selection. Monarchs thrive, while birds adapt, illustrating nature’s relentless push for survival.